(Auto)stitching and Photo Mosaics

October 17, 2025

Overview

In this project, I explored image warping and mosaicking techniques using homographies and interpolation methods. The project involved computing homographies to align images, warping images with nearest-neighbor and bilinear interpolation, and creating seamless mosaics by blending multiple images.

Part A

A.1 The Pictures

I took these three sets of images, trying my best to rotate around the focal point of the camera lens to minimize distortions in the overlapping image segments.

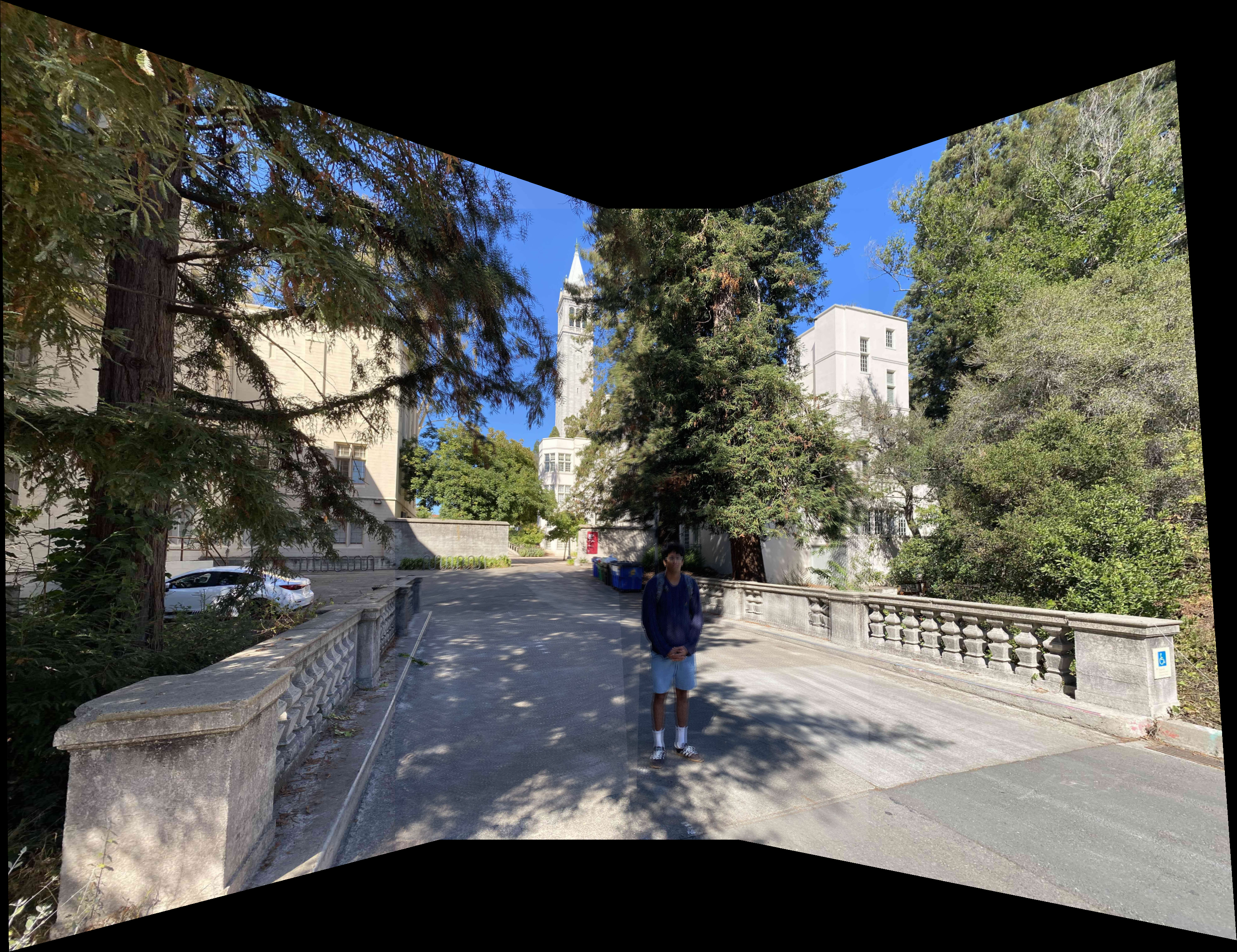

Campanile set.

Room set.

Balcony set.

A.2.0 Establishing Point Correspondences

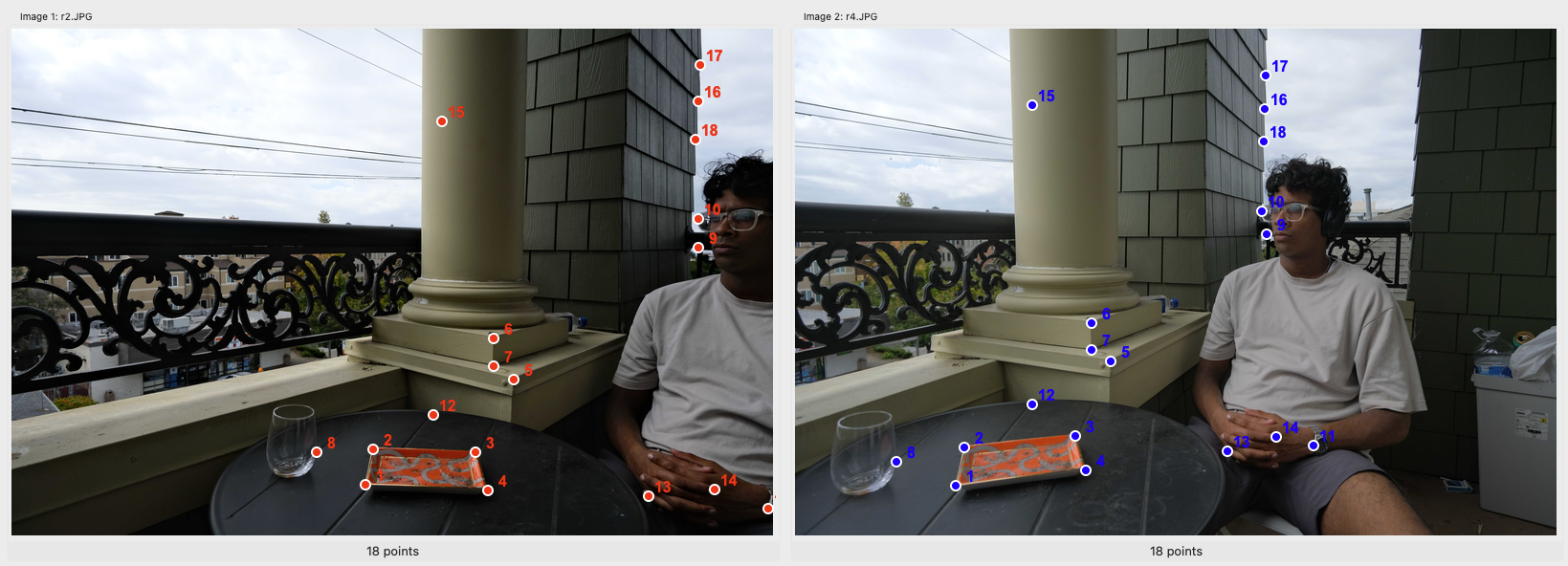

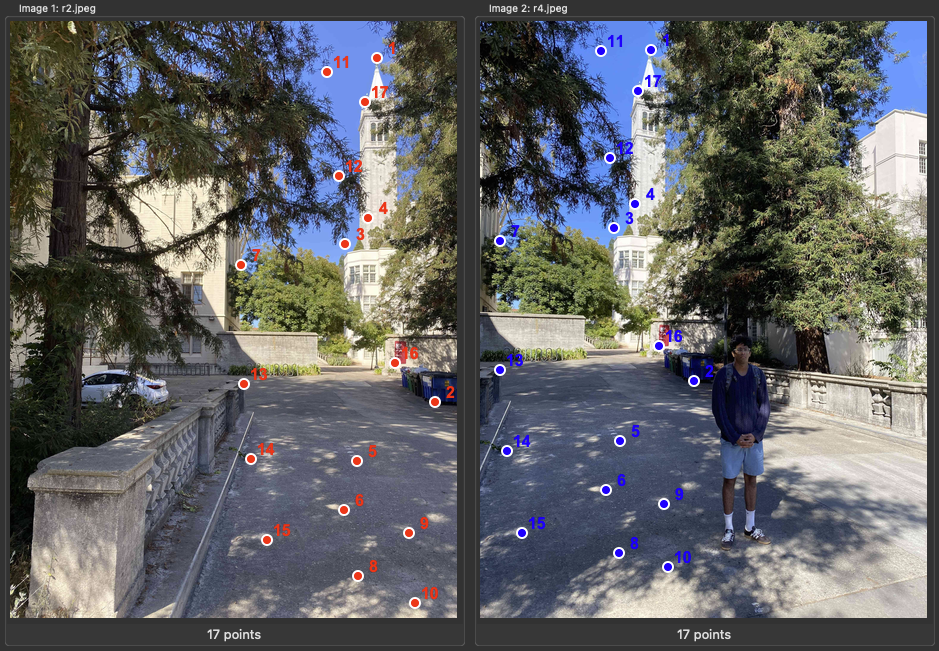

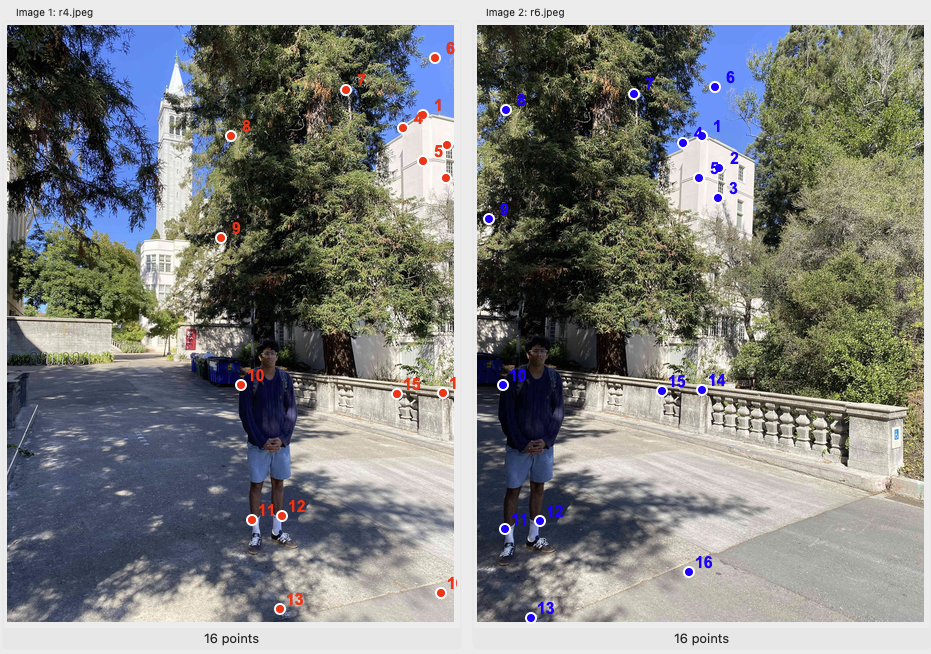

To establish point correspondences, I implemented a Tkinter interface to see to-be stitched photos side by side to find fitting reference points. The interface stores selections for each session in a JSON file. Here are some examples of my point correspondence selection. For stability, I aimed to get 15-20 pairs.

Balcony set point correspondences.

Campanile set point correspondences.

The JSON file is structured as follows:

{

"im1_pts": [

[

2909,

3744

],

[

2971,

3455

],

...],

"im2_pts": [

[

1333,

3751

],

[

1404,

3439

],

...],

}

A.2 Recovering Homographies

To compute the homography matrix $H$ I implemented the Direct Linear Transformation method. This approach essentially establishes a linear relationship between corresponding points in two images and solves for the transformation matrix that needs to be applied to the image using least squares.

For each point correspondence $((x, y) \leftrightarrow (x’, y’))$, the homography satisfies:

\[\begin{aligned} x' &= \frac{h_{11}x + h_{12}y + h_{13}}{h_{31}x + h_{32}y + 1}, \\ y' &= \frac{h_{21}x + h_{22}y + h_{23}}{h_{31}x + h_{32}y + 1}. \end{aligned}\]Rewriting these equations creates a linear system $A h = b$, where $h$ contains the 8 free parameters of $H$ we’re trying to fit to ($h_{8} = 1$). Finally, the solution vector $h$ is reshaped into the 3×3 homography matrix.

My $computeH(im1{pts}, im2{pts})$ implementation:

def computeH(im1_pts, im2_pts):

n = len(im1_pts)

# linear system of equations for all points (solving for 8 unknowns, H_8 fixed to 1)

A = np.zeros((2*n, 8))

b = np.zeros(2*n)

for i in range(n):

x1, y1 = im1_pts[i]

x2, y2 = im2_pts[i]

A[2*i] = [x1, y1, 1, 0, 0, 0, -x1*x2, -y1*x2]

b[2*i] = x2

A[2*i+1] = [0, 0, 0, x1, y1, 1, -x1*y2, -y1*y2]

b[2*i+1] = y2

# solve

h, _, _, _ = np.linalg.lstsq(A, b, rcond=None)

H = np.array([[h[0], h[1], h[2]], [h[3], h[4], h[5]], [h[6], h[7], 1.0]])

return H

For example, for the first and second campanile set photos, our linear equations are:

\[\begin{align} 292.25 &= 621.50h_{11} + 67.00h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 181633.38h_{31} - 19580.75h_{32} \\ 53.75 &= 621.50h_{21} + 67.00h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 33405.62h_{31} - 3601.25h_{32} \\ 364.50 &= 719.00h_{11} + 645.00h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 262075.50h_{31} - 235102.50h_{32} \\ 609.75 &= 719.00h_{21} + 645.00h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 438410.25h_{31} - 393288.75h_{32} \\ 230.00 &= 567.75h_{11} + 379.50h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 130582.50h_{31} - 87285.00h_{32} \\ 352.75 &= 567.75h_{21} + 379.50h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 200273.81h_{31} - 133868.62h_{32} \\ 265.25 &= 606.25h_{11} + 336.00h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 160807.81h_{31} - 89124.00h_{32} \\ 312.25 &= 606.25h_{21} + 336.00h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 189301.56h_{31} - 104916.00h_{32} \\ 240.00 &= 588.00h_{11} + 744.00h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 141120.00h_{31} - 178560.00h_{32} \\ 710.50 &= 588.00h_{21} + 744.00h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 417774.00h_{31} - 528612.00h_{32} \\ 216.50 &= 566.00h_{11} + 826.50h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 122539.00h_{31} - 178937.25h_{32} \\ 792.75 &= 566.00h_{21} + 826.50h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 448696.50h_{31} - 655207.88h_{32} \\ 38.50 &= 393.00h_{11} + 414.75h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 15130.50h_{31} - 15967.88h_{32} \\ 374.50 &= 393.00h_{21} + 414.75h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 147178.50h_{31} - 155323.88h_{32} \\ 238.50 &= 589.50h_{11} + 937.25h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 140595.75h_{31} - 223534.12h_{32} \\ 898.75 &= 589.50h_{21} + 937.25h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 529813.12h_{31} - 842353.44h_{32} \\ 314.00 &= 675.25h_{11} + 865.00h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 212028.50h_{31} - 271610.00h_{32} \\ 816.25 &= 675.25h_{21} + 865.00h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 551172.81h_{31} - 706056.25h_{32} \\ 320.75 &= 685.25h_{11} + 982.75h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 219793.94h_{31} - 315217.06h_{32} \\ 922.25 &= 685.25h_{21} + 982.75h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 631971.81h_{31} - 906341.19h_{32} \\ 208.25 &= 537.50h_{11} + 90.50h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 111934.38h_{31} - 18846.62h_{32} \\ 55.25 &= 537.50h_{21} + 90.50h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 29696.88h_{31} - 5000.12h_{32} \\ 223.25 &= 557.75h_{11} + 265.25h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 124517.69h_{31} - 59217.06h_{32} \\ 235.00 &= 557.75h_{21} + 265.25h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 131071.25h_{31} - 62333.75h_{32} \\ 38.50 &= 398.00h_{11} + 614.75h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 15323.00h_{31} - 23667.88h_{32} \\ 591.25 &= 398.00h_{21} + 614.75h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 235317.50h_{31} - 363470.94h_{32} \\ 50.25 &= 409.75h_{11} + 740.75h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 20589.94h_{31} - 37222.69h_{32} \\ 727.25 &= 409.75h_{21} + 740.75h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 297990.69h_{31} - 538710.44h_{32} \\ 75.50 &= 436.75h_{11} + 876.75h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 32974.62h_{31} - 66194.62h_{32} \\ 865.00 &= 436.75h_{21} + 876.75h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 377788.75h_{31} - 758388.75h_{32} \\ 305.75 &= 651.75h_{11} + 579.50h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 199272.56h_{31} - 177182.12h_{32} \\ 551.00 &= 651.75h_{21} + 579.50h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 359114.25h_{31} - 319304.50h_{32} \\ 270.25 &= 601.25h_{11} + 141.00h_{12} + 1h_{13} - 162487.81h_{31} - 38105.25h_{32} \\ 122.50 &= 601.25h_{21} + 141.00h_{22} + 1h_{23} - 73653.12h_{31} - 17272.50h_{32} \end{align}\]The recovered homography matrix is: \(H = \begin{bmatrix} 1.5833 & -0.0352 & -557.6588 \\ 0.3847 & 1.4279 & -257.9759 \\ 0.0007 & 0.0000 & 1.0000 \end{bmatrix}\)

A.3 Warping the Images

When warping images to align them for mosaics, the transformed pixel coordinates often do not align perfectly with the discrete pixel grid of the input image. To estimate the pixel values at these non-integer coordinates, I tested some interpolation methods. These methods ensure that the warped image accurately represents the input image.

For Nearest Neighbor Interpolation, I rounded the transformed coordinates to the nearest integer values, effectively mapping each output pixel to the closest pixel in the input image. This method is efficient but can result in jagged edges due to the lack of smoothing.

For Bilinear Interpolation, I computed the output pixel values as a weighted average of the four nearest neighbors in the input image. The weights were determined based on the fractional distances of the transformed coordinates from these neighbors. This approach provided smoother results, especially for continuous gradients.

To confirm that the function works, I decided to rectify the third image in the room set, by attempting to horizontally align the poster on the left side of the image.

Left: Original, Center: Nearest Neighbor alignment, Right: Bilinear alignment.

As can be seen, the poster alignment worked, using both warping functions. Next, I tested the functions using homography matrices computed using our correspondence points, warping them to match the perspective of the second image in the set.

Left: Original (1st balcony image), Center: Nearest Neighbor alignment, Right: Bilinear alignment.

Left: Original (3rd balcony image), Center: Nearest Neighbor alignment, Right: Bilinear alignment.

Left: Original (1st campanile image), Center: Nearest Neighbor alignment, Right: Bilinear alignment.

Left: Original (1st room image), Center: Nearest Neighbor alignment, Right: Bilinear alignment.

In terms of runtime, warpImageNearestNeighbor averaged 0.115s, while warpImageBilinear averaged 0.165s. While warpImageNearestNeighbor is faster, it may produce lower-quality results because of its simplicity. warpImageBilinear creates smoother transformations.

A.4 Blending the Images into a Mosaic

Finally, to create seamless mosaics, I used a weighted averaging technique to blend overlapping regions of the warped images. To do so, I determined the size of the final mosaic by projecting the corners of all images into the chosen reference frame. Each image was then warped into this common projection. For blending, I assigned higher weights to central regions of each image and gradually reduced weights towards the edges, ensuring a smooth transition between overlapping areas.

\[I_{out}(x, y) = \frac{\sum_{i} I_i(x, y) \cdot M_i(x, y)}{\sum_{i} M_i(x, y)}\]where $I_i(x, y)$ is the intensity of the $i$-th image at pixel $(x, y)$, and $M_i(x, y)$ is the weight for the $i$-th image at that pixel. This approach minimized edge artifacts decently. Below are my results!

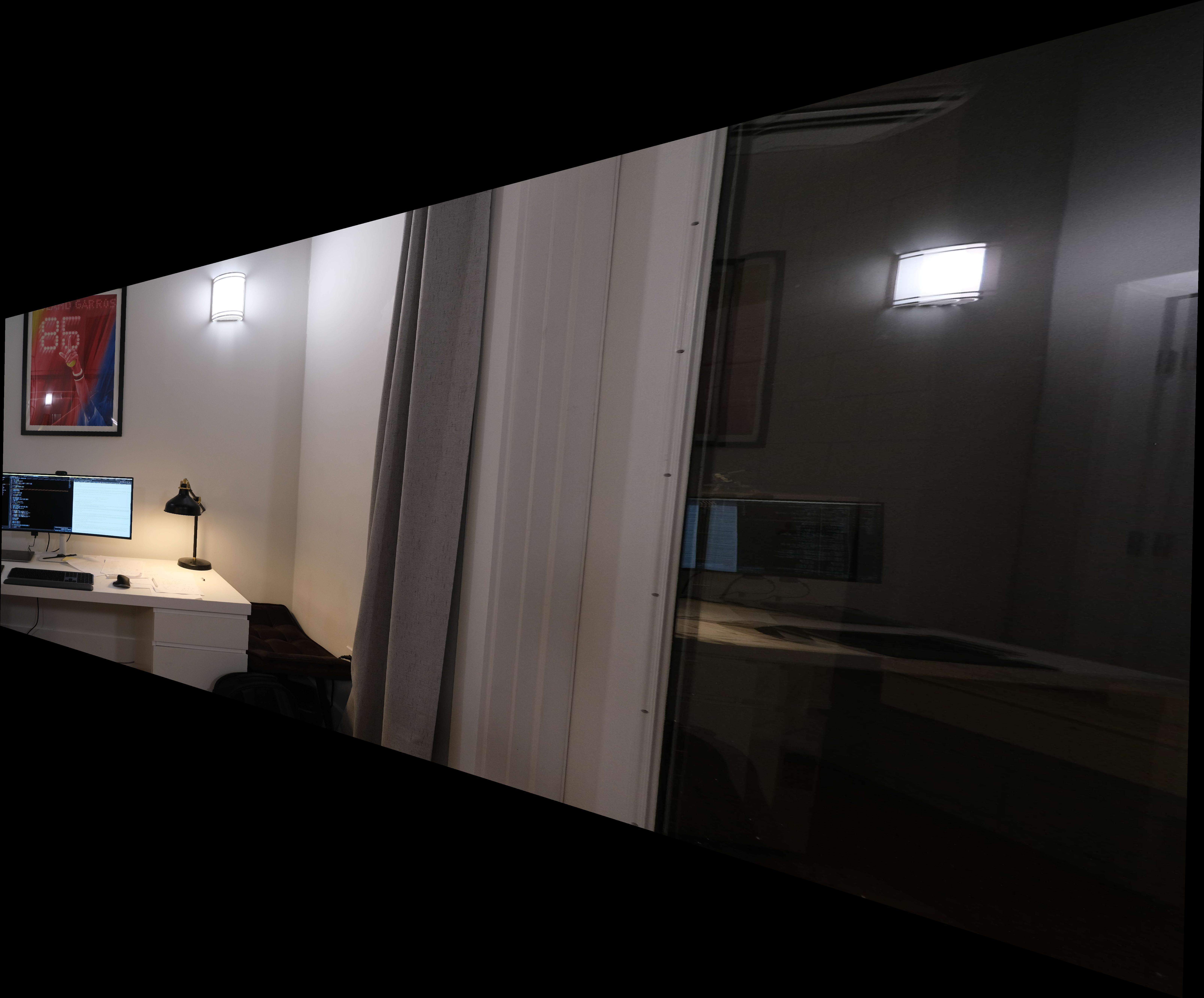

Room Mosaic.

Balcony Mosaic.

Campanile Mosaic.

Part B

In the second part of this project I implemented an automatic image stitching code using Multi-Scale Oriented Patches (MOPS) features, following the methodology discussed in the paper “Multi-Image Matching using Multi-Scale Oriented Patches” by Brown et al.. This approach auomates the point selection process I manually performed in part A. The updated methodology consists of new steps including Harris corner detection to identify interest points, feature descriptor extraction to compare image patches, feature matching, and RANSAC homography estimation for robust alignment.

B.1 Harris Corner Detection

Harris corner detection identifies interest points by analyzing local image gradients. The algorithm computes image derivatives ($I_x$, $I_y$), then constructs the matrix:

\[M = \begin{bmatrix} I_x^2 & I_x I_y \\ I_x I_y & I_y^2 \end{bmatrix}\]The Harris function is given by $R = \det(M) - k \cdot \text{trace}(M)^2$, where $k$ is a manually defined constant for the sensitivity to corners. Corners correspond to regions where both eigenvalues of $M$ are large, indicating significant gradients in multiple directions.

For Adaptive Non-Maximal Suppression (ANMS), I computed the suppression radius $r_i$ (the minimum distance around a corner point where no stronger corners exist) for each corner $i$ as:

\[r_i = \min_{j} \|x_i - x_j\|_2 \text{ such that } f_j > c_{\text{robust}} \cdot f_i\]where $f_i$ is the Harris strength and $c_{\text{robust}}$ is the robustness parameter, ensuring only significantly stronger corners can suppress weaker ones.

Left: Original, Center: Harris detected edges, Right: ANMS edges ($N=1000$, $c_{robust}=0.9$).

B.2 Feature Descriptor Extraction

For each detected corner, I extracted a MOPS descriptor to characterize the local region. This works by first applying a Gaussian blur ($\sigma = 1.0$) to reduce noise, then extracting a large 40×40 pixel area around each point. This area is downsampled to 8×8 pixels using area interpolation to achieve scale invariance.

The descriptor vector is formed by flattening the 8x8 area and normalizing. This normalization ensures invariance to illumination differences between images. Corners with little texture around it (low standard deviation) are skipped for better descriptors. Below is a small subset of some features extracted from the above image’s corners.

Low-frequency descriptors.

B.3 Feature Matching

In the next step, I worked on matching features between images. Feature matching works with nearest neighbor search using Lowe’s ratio test. Specifically, I computed the squared Euclidean distance matrix between all descriptor pairs:

\[M_{ij} = \|\mathbf{d}_1^{(i)} - \mathbf{d}_2^{(j)}\|_2^2 = \|\mathbf{d}_1^{(i)}\|^2 + \|\mathbf{d}_2^{(j)}\|^2 - 2\mathbf{d}_1^{(i)} \cdot \mathbf{d}_2^{(j)}\]For each descriptor in the first image, I identified the two nearest neighbors in the second image. A match is accepted only if the ratio of the closest to second-closest distance satisfies:

\[\frac{d_1}{d_2} < \text{ratio threshold}\]where $d_1$ and $d_2$ are the distances to the first and second nearest neighbors, respectively. This ratio test is intended to filter out ambiguous matches. In my implementation, I used a ratio threshold of 0.8, which provides a good balance between match quantity and quality.

Red points correspond to matches between image 1 and 2, green points correspond to matches between image 2 and 3.

Even with the ratio test, some erroneous correspondences inevitably remain due to repetitive textures, lighting variations, or similar-looking features across different spatial locations.

B.4 RANSAC for Robust Homography

To handle outliers in feature matches, I used RANSAC (Random Sample Consensus) for robust homography estimation. The algorithm iteratively samples small sets of correspondences to find the model that best explains the correspondences while being robust to potential outliers.

The RANSAC procedure works by first randomly sampling four point correspondences. The selection of points is then used to compute the homography using the DLT method from part A. Next, all points are projected from image 1 to image 2 using $H$, evaluating the projection error.

\[\text{error}_i = \|H \mathbf{p}_{1i} - \mathbf{p}_{2i}\|_2\]From this, I counted the number of points for which the error lies below a threshold. Finally, I kept the homography with the largest consensus set.

Below are some comparisons between my manually generated mosaics and the automatically generated ones.

Left: Campanile manual, Right: Campanile automatic.

Left: Balcony manual, Right: balcony automatic.

The automatic stitching sometimes produces lower quality results compared to manual stitching since automatic feature detection may miss optimal correspondence points that humans would naturally select. Also, the limited number of detected features can lead to less robust homography estimation, and the RANSAC algorithm’s random sampling may not always find the globally optimal solution within the iteration limit.

Here are some more new images using the feature matching and autostitching approach I implemented.

Lawrence Hall of Science Mosaic.

Grizzly Peak Vista Point Mosaic.

Clark Kerr Mosaic.

Rohan & Carter Mosaic.

Rohan & Carter Mosaic.

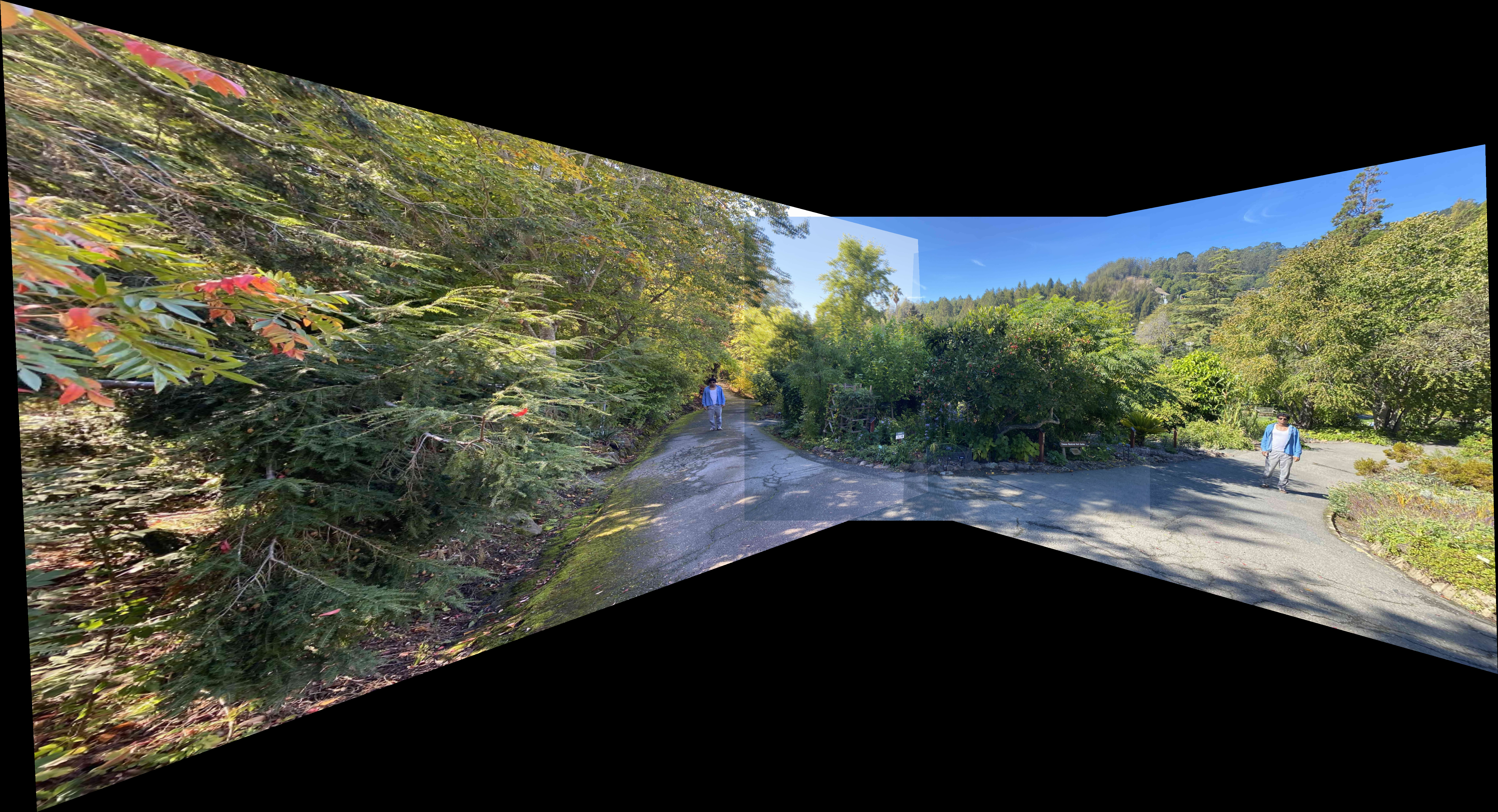

Finally, some fun explorations of the same subject moving into multiple stitched frames:

Multishenoy 1 Mosaic.

Multishenoy 2 Mosaic.